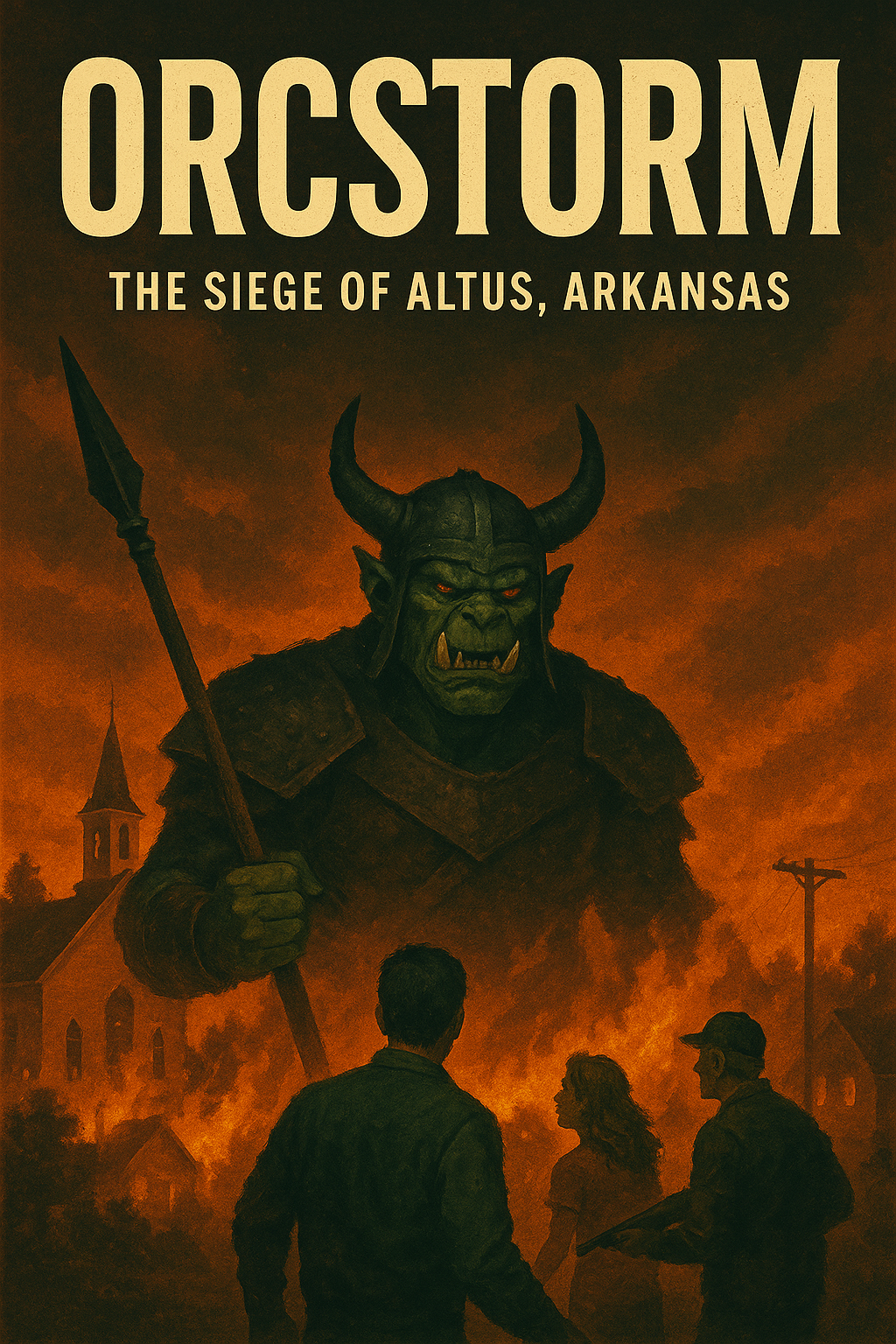

Orcstorm: The Siege of Altus, Arkansas

Deputy Caleb Ward noticed the smell first, pine sap and something sweeter, like copper in blood. It wafted through the August air in the woods off County Road 12. Cicadas shrilled everywhere. At the fence row, a heifer lay split open as neatly as a field dressing. The cow’s eyes were glassy. Her tongue lolled out like something that had tried to crawl away and got stuck.

“Coyotes don’t do this,” he said, mostly to shut up the part of himself that wanted to call it a bear. He was alone and the radio kept hiccuping, spitting static.

Caleb crouched, boot soles squishing in the mud the rain had left behind the night before. He kept one hand on his service pistol because habit was a kind of prayer. The tracks were wrong, wide and splayed, with a nail at the tip of each toe like a goat’s hoof gone bad. They marched in a tight line toward the Ouachita National Forest, big enough to belong to a linebacker, too heavy for a prank.

He backed away, stood, and took a long look at the tree line. The pines leaned and whispered to each other. He thought of the old stories, the ones his grandmother told when he was little, about the forest devils that lived behind the hills before white men ever cut a road through them. Caleb had been an Army MP for four years in Kuwait and Germany, He had the calm down cold. But those tracks threw a weight on his ribcage that felt like being sixteen and seeing a copperhead coiled by the porch light.

On the radio, “Dispatch, this is Ward. I need the sheriff out to Holloway pasture off Twelve. We got a dead cow, looks… ritualistic. Not an animal.”

Hiss, “Copy, Caleb. Sheriff’s in route. You okay?”

“Peachy.”

He took three pictures with his phone and texted them to himself, because who did you send something like that to? His kid brother? His ex-wife? He slid the phone away, tugged the brim of his hat down, and traced the track line with his eyes until the brush swallowed it whole.

He didn’t realize he’d drawn his gun until Sheriff Barker’s Blazer rolled up. The heavy-set Sheriff Barker jumped out of the Blazer and said, “Jesus, Caleb, you look like you've seen the boogeyman.”

Caleb holstered the Glock, embarrassed. “Something tore this cow open. Not coyotes. Not a bear.”

Barker peered, squinting like a man trying to read a price tag without his glasses. He was a big-bellied Arkansas man with a church usher’s voice. “We got boys out here drinkin’ Natty Light and tryin’ to scare old ladies,” he said. “Somebody cut that heifer, dragged her guts. That’s what I say.”

Caleb pointed with his pen at the tracks. “Tell me a drunk carved those.”

Barker’s face changed. Just a small shift at the corners of the mouth. He crouched, put a hand over one like he was sizing up a fish. “Ain’t a boot,” he said softly. “Not any boots I put on.”

A gust of wind brought a smell from farther into the trees. Smoke, and something sharp like pitch boiling. Drums, maybe. Or Caleb’s pulse is doing tricks.

“Bonfire?” he said, and Barker listened, eyes gone to slits.

“You hear that?” Barker asked.

“Yeah.”

The forest breathed out heat. Men didn’t build fires this deep in August unless they wanted to burn down half the county. Caleb looked up. A vulture wound slow circles overhead like a lantern swinging, its shadow slipping over eighty acres of pasture, house, and tin-roof barns.

“Let’s keep this quiet,” Barker said after a beat. “I’ll call Game and Fish. You go back into town, find Grizz if he ain’t already at the shop. Ask what kind of animal makes that track. I’ll follow this line a bit and see what’s what.”

Caleb didn’t like splitting up. It felt wrong. “I can go with you. We…”

“Son,” Barker said, and smiled the smile he used at traffic stops, “I still like to breathe. Go on. And call the tower guy. My radio’s crackling like bacon.”

Caleb hesitated, then nodded and obeyed.

As he drove slowly back toward Altus, population 132 on the hand-painted sign where the whitewash had scabbed off in places, he rolled down the window and let Arkansas in: pine resin, a fawn’s cry by the ditch, tar bubbling on fresh chip-seal. He passed the high school football field, grass gone patchy, the bulldog mascot painted so many times the snout had blurred. He passed the Baptist church with the marquis that said, in plastic letters,TOO HOT TO KEEP CHANGING THE SIGN. SIN BAD. JESUS GOOD. He braked at the four-way where the gas station had a piece of paper taped to the pump: CASH ONLY - CARD READER BUSTED AGAIN.

It was a town where you kept jumper cables in your trunk because you didn’t need to ask who needed them. He had expected to spend this August Thursday telling Mrs. Norris that her grandson’s mud tires were illegal, writing up a dog-bite report, and listening to the radio. The world would oblige that kind of expectation right up until the minute it didn’t.

Grizz McCaffrey’s gun shop sat next to a sagging antique store that sold quilts for the price of a month’s rent. Grizz had a purple heart over the register and six different “DON’T TREAD ON ME” signs in the window because he liked snakes only in pictures. The bell over the door clanged and Grizz looked up from the crossword puzzle and said, “Deputy Ward. I’m respectable today. All my paperwork’s filed and my sins confessed.”

Caleb put his elbows on the glass. “I got tracks,” he said, and showed Grizz the pictures on his phone. Wide, splayed toes. Nail marks. Heavy. Grizz tore off a length of receipt paper and stenciled it over the photo. He stuck the receipt to a scrap of poster board from a stack that had once advertised Coach Norris’s retirement fish fry.

Grizz tapped his front tooth with a fingernail, thinking. “Lord. I ain’t seen this before. Bigfoot people get excited over this kind of thing, but this ain't Bigfoot or a dogman. Maybe a boar? No.” He frowned. “Where at?”

“Holloway pasture off of county road 12. ”

Grizz’s eyelids lifted like a man waking up, grumpy. “Is anyone out there?”

“Barker. He followed it in.”

“Well,” Grizz said, “if you want my sage counsel, I’d rather see Barker with Jesus in his heart than Barker gone into the trees alone. I told that man: I saw lights way back there last week. Flickerin’. Not campin’. Way back. Nobody campin’ in August when it’s 95 at midnight.” He belched.

“What do you need?”

“Rope. Night vision if you got it working. And truth be told…” He paused. He’d come for an opinion and left with a feeling in his bones that was mostly fear. “I have a shotgun. I'd like that rifle.”

Grizz grinned. “Now you’re speakin’ the good Book.”

By the time Caleb left the shop with rope, a borrowed rifle and a flashlight he could club a bear with, the towers were out. Not a hiccup, not a momentary hiccup. Just gone. The radio on his belt spat static and swallowed everything else.

He turned the cruiser toward the Holloway farm and met Barker coming the other way, lights strobing. The Blazer slid sideways on the gravel, corrected. Barker leaned out his window. His face was pale under the brim of his hat.

“Get everyone to the school,” Barker said. “Gym’s our shelter. Call Hannah Price, she’ll know what kids we need to round up if we can’t get the buses rolling. Get Grizz to bring what he can. We’ve got,” he swallowed. “We got some men comin’ down out of the timber. Not a man I've ever seen.”

“Men?”

“Green,” Barker said flatly. “Big. Carryin’, they look like axes if you carved an axe out of a railroad tie.” He breathed hard. “They knocked the tower. They knocked it good.”

“How many?”

“I saw six. Heard more.”

Behind Barker, in the far distance where the pasture lifted toward the timber, Caleb saw a thin smudge of smoke. He also saw, for a heartbeat, a shape at the edge of the trees illuminated by the sun. It was a big man, bigger than Grizz, high as a cheap ceiling, bare-armed, with a chain of teeth around his throat. The skin was not painted. It was the color of river moss, mottled, gleaming with sweat. The jaw jutted like a shovel blade. In one hand he held a spear whose head was a chunk of metal hammered, ugly, and sharp.

The thing lifted the spear, and the tip flashed in the sun.

“Lord have mercy,” Caleb said softly. “We need the State Police.”

“State Police got no phone if the tower’s down,” Barker said. “Go.”

Caleb went.

Hannah Price taught English to tenth graders in a room with buzzed fluorescent lights and a poster that said READING IS POWER over the bookcase she bought herself at a yard sale. She met Caleb in the hall as he hustled the first wave of folks into the gym, the band director with his baton like a sword, the janitor with a mop handle over his shoulder, a half-dozen moms whose faces made him want to cry. Hannah’s blond hair was pulled back in a practical band, and she had Freddie, her beagle, in her arms because the dog had pitched a fit when the tornado sirens started sounding.

“What is it?” she asked, a whisper like church. “I know it isn't a tornado. Is it a fire?”

“Worse,” Caleb said. “I need you to get everyone you can think of who’ll be alone, elderly, or kids whose folks are at work over in Jasper. We’ve got some… intruders heading down from the forest.”

“Intruders?” Her eyes searched his face. She knew the man he was when he said something straight. “Caleb. What kind of intruders?”

“Do you remember the stories our grannies used to tell? The folklore? Forest devils?”He saw his words land in her head and make a mess.

“That’s a story,” she said, too quickly. “That’s a… well.” She inhaled through her nose like she’d gone under in the creek and had to come up quick or drown. “Okay. We’ll do it like a tornado day. I can do that.”

“You can,” he said, and put a hand on her shoulder and squeezed, a departure from the way they had ever touched each other. “If Grizz shows up, let him in and don’t argue when he starts handing out weapons. Lock the west doors and wedge the east and somebody hang a red cloth or something outside so folks know where to come.”

Hannah nodded and ran.

By three p.m. the gym had a hundred and ten people inside: toddlers sticky with juice, old men with canes like angry questions, teenagers who looked like their phones had been surgically removed. The bleachers rattled under the weight of them. The volunteer fire department parked their truck by the east doors and pointed the bumper toward town, hoses looped like snakes. Grizz set up a table with long guns and told people who had never shot more than a dove afterward, “Keep the muzzle down unless you want a hole in the horn of Jesus.”

The lights flickered and died. The generator failed to catch. The gym went to dim. Someone cried and then stopped themselves with a hand over their mouth.

Caleb had people nail plywood over the office windows and stuff towels under the doors. He tapped the radio, useless. He stood in the dark and counted heads. Barker was still up past Holloway with two deputies, trying to slow the thing rolling down.

By five, they heard the first horn.

It wasn’t metal or a truck or anything Caleb could name. It was old and wet-sounding, the note wide and flat, like blowing on the throat of a jug the size of a church. It vibrated the gym floorboards under their boots. Someone prayed. Someone else cussed. Freddie the beagle curled under the bleachers and shook until his tag clinked like teeth.

Hannah stood with Caleb by the east fire doors where a slit of evening shone through the little window. “What if this is just here?” she asked. “Like, what if this is all? What if I call my sister in Little Rock tomorrow and she answers?”

“Then we’ll bug you for a spare bedroom,” Caleb said, because the alternative was to tell her the truth he had a feeling the world outside was breaking the way built things broke when you hit them with the right kind of force.

The second horn came closer. They heard it echo off the Dollar General, off the church’s metal roof, off the water tower that said Altus in faded black. Then they heard a sound below the horn. Drums, dull and bone-thick, like fists on meat.

Then the screaming started down by the four-way.

The orcs came under the cover of a dirty sunset that made Main Street look like the bad part of a memory. Caleb saw them first from the window crack. They ran like linebackers with crash bars. They wore boiled leather and rags that might once have been coats. Their tusks were small in most, bigger in the big ones. Their eyes glittered damply. Some carried axes, some had spears with black tips, some had pieces of rebar with wire wrapped for grip. Two dragged a cell tower guy by his ankles. The man stirred. He was alive, Caleb saw him move, and one of the orcs turned and curtly opened his throat with the edge of a hand as if slicing tape.

“Jesus,” Hannah said without knowing she’d spoken.

Caleb swallowed. His mouth tasted like he’d chewed pennies.

“Positions!” Grizz shouted, voice carrying like he’d trained in it. “You shoot when I say shoot. The women and kids stay down. Shooter line: there and there. Behind the rolled mats. Aim low, knees and hips, I don’t know where their dang hearts are.”

The first orcs hit the east doors and the fire hoses blew them back in a beautiful arc. The water pounded their chests and snapped heads and sent them skidding until they slammed into the curb. The room erupted in a cheer. It died fast. The Orcs shook themselves like dogs. They howled in a language that sounded like rocks. They spread, learned quickly, and came at the windows they could reach with those ugly axes.

The glass shattered. The dark was filled with bodies.

Caleb fired the shotgun once, twice, pumping, aiming center of mass because that was his body’s training, seeing the flinch and the spray like meat hit with a sledge. Grizz shot steadily from the right, barrel rising and falling, cussing without words. A teenager named Wyatt who had looked like a skeleton with a baseball cap took a bead on an orc’s knee and blew it and watched the creature topple so hard it took three more down with it. Everyone was crying or praying or both. Hannah had her arms around two second-graders who had been at cheer camp when this started, whispering stories at a pitch just too low to hear, stories about saints and dragons that held the children where bullets were doing the other kind of work.

For ten minutes the world was gunfire and screams and water and splinters. Then a shadow came through the broken window, tall enough to duck, and the air changed temperature like before a storm breaks. He stepped into the gym with the slow confidence of a man who had never been pushed backward.

He was bigger than the others by a head and a half. His skin was deeper green, almost black where sweat ran. His hair was braided with wire. A scar cut across his nose and down his cheek like a white river. A chain of human teeth clacked against his chest as he moved. He carried a spear. He wore a belt with blue police Arkansas license plates cut to hang like lamellar armor.

“Uzguk!” one of the orcs outside howled like a hound calling to the moon. Then all chanted his name in unison. The drums grew restless.

The shaman came with him: a lean female with a skull cap of something that used to be human and a dress patched from canvas and fur. Her eyes were mud-yellow like a sick dog’s. She put both palms out and the temperature dropped so fast that Caleb’s breath made a fog. The hanging gym banners stirred in wind that wasn’t, and then the lights went out—every candle, every flashlight beam, every thin bit of illumination crushed like fireflies in a fist.

The storm walked into the room with her.

Night fell at six in the evening and stayed. Thundersheet grumbled just outside the windows. Rain hammered the roof and stopped and hammered again. The whole world felt bent, like someone had taken the gym in their hands and twisted.

“Shara,” Hannah said softly, like a story book closing. “That’s the name. The old woman said it.”

Uzguk planted the spear butt on the gym floor so hard that the varnish cracked. He looked over the people in the bleachers and the people behind the mats and smiled with a mouth that understood what it was to rip something. When he spoke, the language wasn’t English but Caleb felt the meaning anyway, the way you feel thunder without seeing lightning.

“Give me the house,” Uzguk said. “Give me the field. You took them. You forgot.” He tapped his chest, the teeth clicking. “We were here. We go under the ridge and eat pine bark. We sleep and wake and sleep. We hear your engines. We smell your grease.” He pointed with the spear at the rafters, at the banner that said 1997 DISTRICT CHAMPS. “You build your pictures. Give to the Orcs.”

Nobody moved.

Grizz lifted his rifle and yelled, “Go to hell, Shrek,” because if you could make a joke...

Uzguk’s spear blurred. Grizz staggered, looked down at the shaft in his belly like it had materialized there by magic, and dropped to his knees. He made a sound like a deer. Hannah screamed. Caleb fired and fired and one pellet grazed the shaman’s face and she hissed and put out both hands and the air rippled like heat and the shotgun bucked out of his grip and skidded twenty feet.

Then Caleb remembered the stories. Forest devils that couldn’t stand iron nails buried crosswise in the threshold. Grandma’s voice cracked like dry leaves: “They’re older than the Cherokee. Older than the hills, baby. They were here when the dirt was still deciding where to sit. They hate the sound of a bell, too. They hate it bad.”

Caleb hauled himself toward the equipment room, boots slipping on blood and water, and in the dark, he pawed through boxes until his fingers found a weight: the old hand bell the principal used at pep rallies, heavy brass with a wooden handle. He came back into the gym and put himself between Uzguk and the bleachers because sometimes stupid was the only bravery there was, and he rang the bell.

The sound wasn’t that loud. It was a school bell. But it slid through the storm noise like a clean thread and it hit Uzguk in the ear and he flinched as if someone had put a hot nail to his neck. He took a step back and the teeth chattered harder. The shaman made a snarling sound that was both word and animal.

Caleb rang the bell again and yelled, “Get back!” and to his surprise, some of the orcs did, a stutter in their forward rush, like he’d put a fence they couldn’t see between them and the bleachers. The kids were crying openly now, and the bell said this is a school, this is ours, this is Arkansas, this is the last place on the map you can bring a storm in and write your name.

“Old tricks,” Shara said in something like English, voice raspy. “We learn new.”

She clapped her hands. The bell handle split in Caleb’s grasp. The brass cup shattered on the floor, and the sound that came out of it when it died was small as a penny dropped, and then the night fell harder.

He thought, We’re going to die here. He thought, This is it.

He did not drop. He grabbed a girl by the wrist, Hannah’s student, Cora, who’d been passing notes about kissing the boy who bagged groceries at the J-Mart, and he dragged her backward while the orcs came through the mats and over the mats and into the breach. He felt something grab at his leg and kicked and didn’t find flesh. He lost count of the shots the defenders had left. He saw Uzguk wade toward the bleachers with the steady gait of a man at a river crossing.

Caleb threw himself at Uzguk. No plan. Like diving on a grenade, you did it and then figured out why. He hit the orc at the hip and bounced like rubber. He grabbed for the belt, found license plates, found edges like teeth, got his fingers under, and yanked. The plates came away and did nothing.

Uzguk looked down at him with amusement and something else. Recognition? No. Respect? A little. Then he palmed Caleb’s face and pushed, and the world tilted, and Caleb rolled sideways and his ribs flared white.

“Caleb!” Hannah’s voice cut through the thunder.

He got his knees back under him. He saw Hannah on the bleachers with three kids behind her and a kitchen knife in her hand from the concession stand. Her chin lifted. It made Caleb want to kiss her because it was the bravest thing he’d ever seen. She said something in the old words, not Cherokee, not white, the nothing-language of their grandmothers. Shara’s head snapped toward her.

“It’s not gone,” Hannah said, and for a second her face looked older than he had ever known it, scribed with lines that were not there. “It never left. You don’t get to take what we fed.”

Shara smiled with too many teeth. “Witch,” she said, liking the taste of it.

Hannah raised the knife. Her hands were steady. Shara made a small, flicking gesture and a wave of cold rolled over the bleachers that knocked the breath out of a dozen chests. The knife fell from Hannah’s fingers like a dead sparrow. Cora screamed. Uzguk lifted his spear.

Caleb got to his feet with a very specific clarity: he would not see Hannah die. He could take the spear. He’d taken worse in the service of things, not really, who was he fooling, but he could do this one small thing.

He lunged. He put his body in line and caught the spear under his ribs. Time went thin and crystal. He felt it pierce his skin. He felt his shirt damp. He held onto the shaft with both hands so Uzguk couldn’t draw back and strike again. He saw Hannah’s mouth make a sound he could not hear and then Freddy the beagle flew out from under the bleachers with the kind of insane bravery dogs have when the things they love howl. Freddy went for Shara’s ankle. He sank his teeth and shook. Shara screamed.

Her screams changed the room. The Orcs flinched. The storm stuttered. The lights flickered. The generators coughed and died again but the brief flicker gave half the shooters their sights and they put bullets where they had been praying to put them for nine minutes. Two orcs went down hard, one with his mouth trying to say a prayer in a language older than the hill. Uzguk wrenched the spear. Caleb screamed and fell to the floor.

Suddenly, the gym doors gave in a run of splinters and the crowd broke. People ran in every direction because there was no direction left. Shara’s black magic, her spell that had held everything together had dissipated.

What followed was not a battle. It was a slaughter with pockets of resistance: Grizz propped against the table, gray and green with a rifle that still cracked, cracking, cracking until it didn’t; Ms. Delaney from the pharmacy using a folding chair like a lion tamer and getting two kids past an orc’s knees into the hall where they vanished into sirens that were not sirens but the blood in Caleb’s ears; the band director stabbing a reed knife into the back of something that smelled like musk and old pennies, crying “B flat, B flat” even as he cut.

Hannah did not use the knife again. She got three kids into the girls’ locker room and barred the door with the aluminum bench and sang, very softly, Amazing Grace, because she could not think of anything older. Shara put both hands to her bleeding ankle and said a word that made the bolt in the door slide back like a trust broken and then the bench moved by itself and Hannah looked in her face in the mirror. The face of a woman who had taught vocabulary words while planning funeral casseroles, and she smiled because the smile was the only power she had left and it spooked the devil, and she got two of the kids out the back. The third, Maddie, hid in a shower stall and put her hands over her ears and did not come out again, ever.

Caleb crawled. He lost the spear out of himself and didn’t know how or when. He left a trail that he didn’t want to think about. He found Grizz slumped and said, “Hey, old man,” the way soldiers say hello so the dead will wait their turn. Grizz’s eyes were open. He tried a joke and made a burble instead. Caleb took his hand and said, “I know,” and then he ran out of things to say.

He found the principal’s office dark and the glass door spidered and a box of iron nails on a shelf because the shop class had been working on footstools. He spilled them. He cut his hand open on one and pressed his bloody palm to the seams of the floor and the nails to the seams of the door and he said the older words in a voice that was probably just hoarse English and he made a cross on the threshold with his blood because sometimes the superstition in you has more room to breathe than the science, and the next orc that came snorted like it smelled something it hated and turned away.

They murdered Altus in an hour. They did not burn it that night. They took meat and they took trophies and they raised their horns and blew them until the deer in the woods lay down out of terror. They dragged off what they wanted and left what they didn’t. Shara put her hands on the sky and pulled the clouds down to the tree line until you could smell the rain but not get wet.

When morning finally came, gray as dishwater, quiet as a truck with no keys, the gym was a wreck of spent shells and splintered benches and bodies covered with the blue tarp from the baseball field. Caleb sat with his back to the cinderblock wall. He woke when Hannah touched his shoulder. He didn’t know he’d slept. He wished he hadn’t.

“How many survived?” he asked. His voice was a rusted hinge.

“Not enough,” Hannah said. Her hair had come down, and it made her look like a girl in a way that hurt. Freddy was alive, sitting with one paw in the air like it hurt to put it down. He had blood on his muzzle and eyes that had seen too much.

They had maybe twenty survivors. Maybe fewer. Old man Jose with his harmonica. Wyatt with the cap, shaking hard and not saying words correctly. Ms. Delaney, who had kept three children under the bench and told them the story of Daniel and the lions in a voice that did not shake. A few more from houses at the north end who had hidden in the storm cellars while the horns blew. The church lady who pasted the letters to the marquis. The deputy with the bad knee had arrived in the last five minutes when it was already too late to be on time.

Of the rest, Barker was slaughtered in the pasture; the cell tower guy; thirty-five in the gym; five missing kids who would not come back. They were stories for all of them and hands to cover them, but not the right words to say goodbye. The town sounded hollow, like the inside of a drum struck once, hard.

Caleb stood with a grunt. The dope in his veins that made the pain fuzzy had thinned out. What was left was clearer. He strapped Grizz’s rifle on his shoulder and picked up the broken bell because he could not make himself leave it on the gym floor. He tied a rag around his side. He looked at Hannah. She looked back. They did not have to say what they were planning. It was what you did when something bigger than you took what you loved. You went after it and tried to take it back. Piece by piece if you have to.

They gathered a handful who could walk and shoot. They left the ones who could not in the locker room with Ms. Delaney and the church lady, with directions about the storm cellar and instructions to light a fire when smoke meant help.

They went into the trees. They went for the children.

The Ouachitas closed around them with that hot-green smell of August and the blue droning of cicadas climbing up the day. The storm had looked like it broke, but in the shadows, the air held a taste of iron. Shara’s work, Caleb thought. He followed the tracks, huge and splayed and undeniable now that he had seen who made them, through kudzu and a creek that ran shallow, past a cottonwood struck by lightning sometime in the night.

In a low place where the fern grew thick, they found a circle of stones marked with sigils that made the eyes ache. Hannah knelt and didn’t touch anything but traced the lines in the air, and when she did the air trembled. “Old,” she whispered. “Older than the courthouse. Older than anything we built.”

Further on they found a fire ring burned to a black bowl and a spit still slick. Freddy went stiff and growled and Hannah clamped a hand on his ears. Caleb’s stomach turned until he had to bend over and spit bile into pine straw. Wyatt gagged. The deputy with the knee sat down suddenly and didn’t get back up for a long minute.

They did not find Uzguk. They did not find Shara. The woods swallowed the tracks like they had never been there in the first place. But in a low cave under a ledge of sandstone, they found something else: a wall of chalk drawings in charcoal and animal fat, stick-figure men with guns and hats, stick-figure orcs with spears, a river drawn like a black snake, and a circle with lines for a sun that had teeth. In one corner, a line of figures went into a hole. They came out changed, bent. The picture made a humming in Caleb’s head.

“We woke them,” Hannah said, staring. “Or they woke up whether we wanted to. They have been down here longer than humans have been on the continent.”

“Then we put them back asleep,” Caleb said because it was the only way to say: We might die, but we will not give them our home for free.

They did not do it that day. They did not do it in a week. They went back to town and buried their dead and boiled the water and counted bullets. Somewhere a National Guard convoy found a road that wasn’t blocked and heard a radio that still worked and somebody said “Altus” into a handset with a voice that wept.

At night, horns blew in the pines, closer than they wanted. Once they saw a shape at the edge of the football field, tall, still, watching the moon on the grass. It did not come closer. It was not gone when you blinked. It did not pretend to be a deer.

“Caleb,” Hannah said one night when the clouds were low and a dog barked twice and stopped. “Tell me we can do this.”

“We can do this,” he said.

“You believe that?”

He let the truth come slowly, because he didn’t think lies helped when the monsters wore their faces outside. “I believe we’re not done,” he said. “I believe it kills them to hear a bell. I believe iron still matters and words are older than bullets sometimes. I believe Grizz is laughing at us from wherever fools who stand up too straight go. And I believe if we’re not the first wave, we might as well be the one that made the next one possible.”

She nodded and wiped her eyes with the heel of her hand and he loved her then without hope. Freddy sneezed like punctuation. The water tower stood over them with Altus flaking off in the moonlight. The dark breathed at the edge of town like something settling in for a long sleep or a long siege.

In the morning, he drove past the Baptist church where the marquis letters lay scattered in the grass like teeth, and he picked them up one by one and put them back into the slots with fingers that bled a little from the cuts. He spelled out a thing the town could look at when it was tired:

WE ARE STILL HERE

He stood back. He looked at it. He listened to the cicadas. He smelled the pine. He thought of Uzguk’s spear, the chain of teeth, and Shara's yellow eyes. He thought of the bell shattered on the gym floor and the sound it had made before it died. He closed his eyes and rang it again in his head. He did not hear a horn.

They had lost Altus. In the book of the county, they would write “razed” with a tidy pen. But in the way that places continue if somebody walks the perimeter with a rifle and a prayer, they're not finished. The forest devils had come roaring out of the ridge like something the earth had burped up, and they had taken what they wanted and gone back for a night. They would come again. They had left a handful alive because that was how the siege worked, let them tell the story before you break the rest.

Caleb put his palm on the warm hood of his cruiser. He could see the edge of the woods from here. He watched closely, the way a man watches a door he knows will open. He thought of the old drawings and the line of figures going into the hole and coming out bent. He thought of how you bend something back: slowly, by heat, with patience, with the right words.

“Alright,” he said to the pines. “We’re here.”

The woods said nothing. The world did not offer a sign. The cicadas sang that endless strip of August like it was the first and last song. The day got on with its hot, ordinary business.

Behind him in the gym, somebody rang a little brass handbell they’d found in a teacher’s desk. The note was thin and stubborn and it hung on the air longer than sound has any right to. The bell rang again like a dinner bell. Two National Guard trucks had arrived to evacuate the survivors, shaking the ground as they rumbled to a stop.

Out in the trees, something shifted in discomfort and took one step back. Not far. Just enough.

You took what you could get. Then you made it matter.

0 Comments Add a Comment?